I’m really starting to like ugali. It’s a moist, cakey dish made from corn, and a staple of the Kenyan diet. Everything goes with ugali. It is to Kenyans what bread is to many Americans. I’d never eaten it before coming here for the first time in 2018. I’d never even seen it before. The most important thing about ugali is that it is inexpensive and fills you up. In a context of such vast need, that is no small matter. Not all Kenyans are poor, of course, but many are. In Nairobi alone, about 3 million people live in slums.

Over lunch, some of the American pastors from our Kenya team debriefed on their experiences. While three of us had stayed in Nairobi to teach, others had journeyed through different parts of Kenya meeting with pastors and laity, creating relationships, assessing needs, and trying to understand all that was happening around them.

How do I bring this back to my church? one asked.

I wish I had an answer. I’ve tried, with only limited success. No presentation before the congregation, no YouTube video, no Zoom call can recreate the experience of immersion in a world that is not your own. Those experiences change you. When you come to a place like this, you are never the same afterward, and that is a good thing. Your vision of the breadth of human life has grown. You may grow in your desire to understand others. You may grow in compassion and your awareness of the severity of the conditions in which so many people live around the globe.

It’s hard to convey what life is like here because it is so different than what many of us in the U.S. have experienced. This is my third time in Kenya, and each day is a new adventure in remembering that I don’t know what I don’t know. The people here are patient with me. I’m trying to learn the culture—when to eat and when not to; where to sit; how to show respect; how to avoid disrespect; how to dress appropriately for teaching, church, and casual appointments. Yet one cannot replicate a lifetime of cultural formation in a few short visits. It is madness to try.

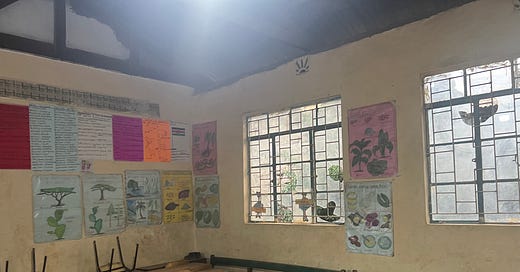

I’m here teaching about Methodism, helping my students develop a deeper understanding of what it means to be orthodox Christians of Methodist extraction. Teaching cross-culturally is hard. I don’t read the cues well. The students here are deferential. American students? Not so much. In a culture where I’m unfamiliar with the classroom conventions, it’s hard to know what’s working and what isn’t. Over time, however, my students here open up a bit, particularly when it comes to matters that affect the day-to-day life of the church.

One hot topic here in eastern Africa is marriage, and especially polygamy. This caught me off guard. I had certainly not prepared notes on polygamy. I knew polygamy was common in Africa, but I had no idea what a pressing concern it is for the Christians in that context. I’m not talking about three Seattle hipsters who decide to turn their polycule into a throuple. Polygamy is an ancient practice and deeply embedded through much of Africa. Yet the Christians here are trying to be faithful to the teachings of the church: one husband, one wife. The topic of marriage came up in one of my classes and the conversation careened into a ribald discussion.

Professor, if a man has two wives and he becomes a Christian, should he divorce one of them when he becomes a Christian?

Wait… what?

And if they do not divorce but they all become Christians, can the man be a leader in the church? Can the wives? What about the first wife, since she had no say in whether or not the man married the second wife?

I’m used to getting difficult questions in class. It’s rare, however, to get a question I’ve never even considered before. I stare at my shoes. I fidget. I try not to look as useless as I feel. Finally some fumbling answer comes forth. It probably isn’t fantastic.

In the U.S., we have our own problems with marriage, but not normally these. The challenges of ministry are contextual, even if there are principles we can apply cross-culturally. We all face thorny problems in our ministry contexts—ethical, financial, and theological problems, among others. These require maturity and theological grounding. Theological education can help as long as it is available, affordable, and contextually relevant.

My students are good people. They love Jesus. They love the people in their congregations. They have lived through hardships that many of us in the U.S. have never considered. They want and deserve to be partners in ministry with Christians from around the globe. They want to learn. They want to teach us as well. If we are wise, we will listen.

To be a global church is no minor ambition. It involves far more than funding, building projects, and a shared polity. In the church, we are all part of one body. The eye cannot say to the hand, “I have no need of you,” nor the head to the feet (1 Cor 12:21). To be the body of Christ is an exercise in mutual submission (Eph 5:21). Exactly what that looks like is often unclear. How do we go forward in humility? How do we use our resources most responsibly? What kind of engagement is helpful, and what does harm, even if inadvertently? What do different groups in the body of Christ have to teach one another? How can we hold one another accountable? How can we love one another, especially when that requires patience and difficult conversations?

If we really want the church to be global, these are the kinds of questions we will need to ask ourselves again and again across time. We will have to cultivate wisdom through prayer and make difficult decisions. We will have to give of ourselves and receive from others when our pride may get in the way. Americans are not perfect, nor are Kenyans, nor Koreans, nor Costa Ricans, nor any other nation or people. We are all sinners redeemed by grace, and we can grow in relationships of mutual love and accountability.

The church is a glimpse of the new creation, however incomplete. Thus as we build the church, we bear in mind the eschatological vision of heaven that God showed to John of Patmos in Revelation 7:9-10:

After this I looked, and there was a great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, robed in white, with palm branches in their hands. They cried out in a loud voice, saying, ‘Salvation belongs to our God who is seated on the throne, and to the Lamb!’

People from every nation, all tribes and peoples and languages, standing before the throne and praising God…. May it be so, not only in the age to come, but even today as light amid this present darkness.

Thank you, DR. Watson, for this enlightening article about cross-cultural Christianity. Even here in the USA, with the migration of various people groups from various cultures from around the world, regardless of where we live, our local assemblies will eventually have to effectively deal with these issues. It can be either a blessing or a curse dependent on whether we’re properly prepared or not. The fact that the GMC aspires to truly be globally inclusive puts it ahead of the learning curve. We need to pray that this intentionality can properly seep down into the local congregations.

Thank you for a powerful reminder (from your firsthand cross cultural experience) that we will need a big dose of humility and teachability as we walk alongside our international brothers and sisters in ministry. The Holy Spirit has much to teach us all; may it not only unify us, but sanctify us as we listen to one another.